Cecil Graham: What is a cynic?

Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan

Lord Darlington: A man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.

Cecil Graham: And a sentimentalist, my dear Darlington, is a man who sees an absurd value in everything and doesn’t know the market price of any single thing.

Many seem to have an instinctive distrust of the idea of evaluating and pricing things that once seemed intangible but the circular economy depends upon creating markets in which waste is seen as a valued resource. If this is to happen, there are two preconditions.

Firstly, there must be a means by which the value of waste can be realised by turning it into something with a cash value. This is the revenue part of the equation and so it’s the part that’s most exciting because it’s the most tangiable.

Secondly, there must be a means by which costs are internalised. This is the costs and overheads part of the equation and so, as always, it seems dull by comparison; the province of ‘bean counters’ rather than marketeers and innovators. However, this is where so much change needs to happen because this part of the equation is where the real circular economy lies.

Our new study, Growth within: A circular economy vision for a competitive Europe provides new evidence that a circular economy, enabled by the technology revolution, would allow Europe to grow resource productivity by up to 3 percent annually. This would generate a primary-resource benefit of as much as €0.6 trillion per year by 2030 to Europe’s economies. In addition, it would generate €1.2 trillion in nonresource and externality benefits, bringing the annual total benefits to around €1.8 trillion compared with today.

McKinsey and Company – 2015

As the McKinsey and Company report says, ‘non resource and externality benefits’ are worth 2x more than the primary resource benefits. So, in progressing the transition to a circular economy it’s going to be essential that these benefits are understood and accounted for. Crucially, this isn’t just at a macro-economic level but at a company level too. The level of exposure that a corporation has to the risks and benefits of externalities is fast becoming critical to the way in which the financial world sees their viability.

Cut the jargon

“Cost internalisation is the incorporation of negative external effects, notably environmental depletion and degradation, into the budgets of households and enterprises by means of economic instruments, including fiscal measures and other (dis) incentives.”

OECD Definition 1997

One reason that ‘cost internalisation’ and ‘externalities’ get overlooked is that they are cloaked in so much economic jargon but the concept is quite straightforward.

As I wrote in my in my previous post, ‘negative externalities’ are costs suffered by a third party as a consequence of somebody else’s economic transaction. In a transaction, the producer and consumer are the first and second parties. Third parties include anyone that is indirectly affected by that activity (usually negatively). Some externalities, like waste, arise from consumption while other externalities, like carbon emissions from factories, arise from production.

When a producer recognises and takes account for those externalities, they internalise those costs and so treat them as they would any other business overhead.

So, in the linear economy producer responsibility ends at the point of sale, and they protect themselves from the cost of externalities by minimising the support that they give to the consumer post sale and taking little or no responsibility for the product at the end of its life. If the resulting material scarcity forces producers (and consumers) to become more resource efficient, these costs must be dealt with rather than avoided and so business models change toward ones that can be supported through service revenues, product performance and material recovery. After all, this is the fundamental driver of the circular economy.

Dependency or consequence?

In thinking about corporate sustainability, we often talk about the impacts of a product or process. We measure GHG emissions, water usage and demand that companies report on these. In this way, corporate culture has shifted to one that owns these impacts (often grudgingly) and sees the need to act to reduce them. However, what is a more significant change is the dawning realisation that externalities are not just a question of accounting for the consequences of trade but accounting for the fact that the company is also dependent upon externalities like the health of the Earth’s ecosystem.

Ecologists refer to ‘ecosystem services’ as the catch-all term for the benefits that humans gain from the natural environment and properly functioning ecosystems that support agriculture, the marine ecology and forests. The depletion of natural resources, the effects of climate change, access to clean water and agricultural land, all have direct economic impacts on a global scale.

So, it’s logical to recognise that the more dependent that a company is on the world’s ecosystem, then the greater the risk to that company’s future becomes. Also, it follows that the more that a company can do to reduce these dependencies or manage them more efficiently, then the risk to the commercial sustainability of that business is reduced.

In the modern world, a company is linked to rest of the global economy, society and environment in ways that were unforeseen just a few decades ago. A typical modern company is now part of a value chain that is increasingly complex; depending upon indirect relationships both in the ‘upstream’ supply chain and ‘downstream’ where its products are distributed and used. These relationships, from the growing or mining of basic raw materials to what happens to the product at the end of its useful life, all involve activities that have environmental impact of some kind, be it large or small, direct or indirect. Even when a business doesn’t have direct control over these activities, they still have a direct bearing on the company’s products and therefore have a direct bearing on the long-term viability of a business.

Why are so many large institutional investors divesting themselves from fossil fuels? It is more from the realisation that they are simply not a sound long-term investment than it is from a growing green awareness.

Which means that…

Let’s get practical. If a company wants to be successful in the circular economy, they must internalise costs, but how does one do that? What is my company’s portion of humanity’s overconsumption?

“Accounting is the nuts-and-bolts field that tracks the inflow and outflow of money, while economists are typically more concerned with the big-picture trends that drive money.“

Investopedia

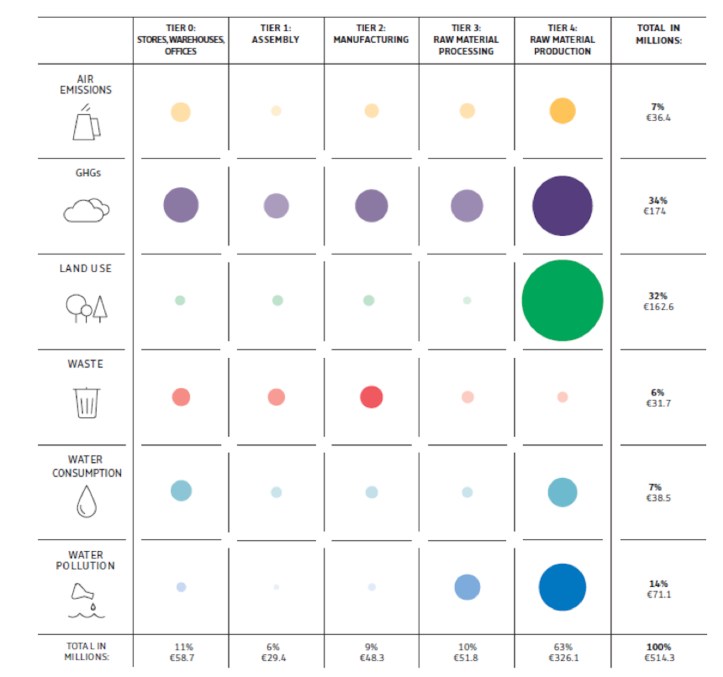

An Environmental Profit and Loss account (EP&L) is a method for placing a monetary valuation on a company’s environmental impacts, including its business operations and its whole value chain.

An EP&L allocates a cost of all those activities to the company by accounting for the value of the ‘ecosystem services’ that producing that product has incurred. This valuation is based upon principles and methods that have been developed under the auspices of the United Nations and so there is a global standard on which these costs are derived, meaning that direct comparisons between EP&L accounts can be made.

Whereas a business has traditionally thought of the cost of its products in terms of materials purchased and company ‘overheads’, an EP&L allows managers and stakeholders (like investors and customers) to see the magnitude of these impacts and where they occur in the value chain.

By giving managers such a clearly comprehensible metric, EP&L becomes a tool to:

- Express environmental impact in terms that all businesses understand – £, $ and € rather than metrics like “kg CFC-11-eq”

- Engage the supply chain on environmental issues in a way that is material and relevant

- Compare different impacts which are not otherwise comparable

- Compare brands and business units

- Make better-informed operational decisions through the ability to measure return on investment that includes environmental aspects

- Improve risk management by highlighting the potential consequences of environmental dependencies

Given all of these benefits, it is not surprising that investors are increasingly looking to companies to be able to disclose their EP&L and that there’s now a direct link between a business’s access to capital and its ability to show its exposure to environmental risk.

Making it happen

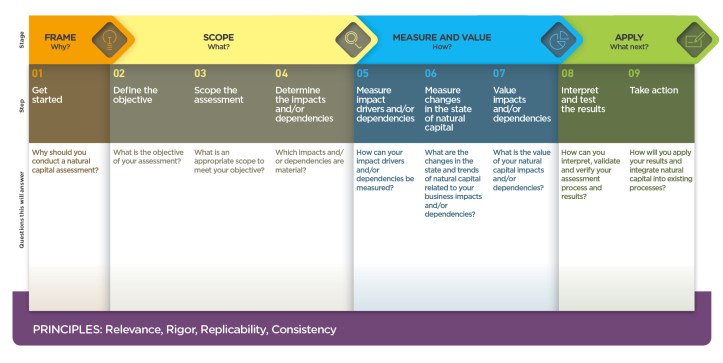

There are many case studies available that show how businesses have applied the methods of the Natural Capital Protocol. The methodology is proven and supported by excellent resources from the Capitals Coalition.

The best example by far is still the visionary work begun by Kering. The methodology that they developed along with PwC is comprehensive, applicable, transparent and freely available.

The thing that many companies find daunting in creating an EP&L is gathering the data. However, in my experience, that data is often more accessible than many believe.

The primary data that is required to carry out an effective EP&L is already available within your organisation. It lies within ERP systems, purchasing records, Excel spreadsheets and other records that are kept by managers in all organisations, right down to facility level. So, in order to access the data, it is important to engage people from across the organisation into a small cross-functional team. After all, if one of the benefits of making an EP&L is to make everyone in the company realise that they have a contribution to make in making the business more sustainable, then why not involve them from the beginning in the exercise?

In making their EP&L, Philips needed to gather just 10 data sets from each of their facilities and all of them were readily available from within their own operations. What then turns these data sets into an EP&L is the way in which they are linked to natural capital impacts calculated through scientifically verified data.

Where can tech help?

As I discussed in an earlier post about overcoming the cold start problem, there are ways in which AI companies can overcome the daunting prospect of data collection so that the clever parts of data wrangling can begin. What is currently missing is an offering that will process the data efficiently and accurately. A software product that can find the best secondary data sources and apply the EP&L methodology to produce compelling and truly applicable ESG reports.

The detailed PwC methodologies used to produce the Kering EP&L are freely available. Indeed, here’s a copy for you to download and digest but please be aware that it is over 400 pages long.

Like so many other processes that we now take for granted, EP&L is complex but perfectly logical. The purpose of good software has always been to break down these processes and guide any competent user through them so that they can see the true value of everything.